It has become somewhat traditional for me to review the Spherical Model on the last post of the year. (Also at other times, such as early March, the anniversary of when I started the blog in 2011.) I’ll get to that eventually. But I want to lead into that by first talking about a podcast I was listening to the other day.

The host of Cwic Show is Greg Matsen, and the person being interviewed, Julie Behling, did her master's thesis on the underground Christian churches in the Soviet Union. She is the author of Beneath Sheep's Clothing and has a documentary with the same name coming out in January.

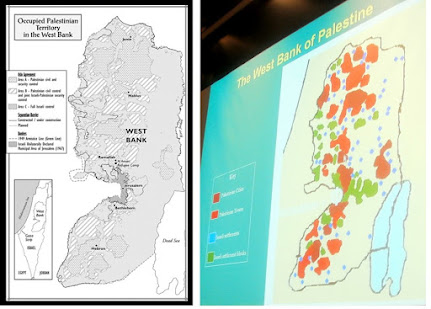

|

| screenshot from Cwic Show December 15, 2023 |

One detail I hadn’t known about the Soviet Union was that

the KGB had infiltrated the churches. All of them. The clergy were either

cooperating with the KGB, or they were KGB agents. Behling offers details

about how they had done this, and why. But it came down to controlling what

people believe, because that is what totalitarian tyrannies must do.

Then she added that, in her research, she was somewhat

shocked to find that Communists had also infiltrated a solid half of American

Christian churches, more than a century ago.

She mentioned Dietrich Bonhoeffer, a German pastor, who

spent some time in the US in the 1930s (I wrote about him here), who was sad to come to the Union

Theological Seminary only to find that they scoffed at the idea of Christ’s

divinity and atonement for sin. Those were the same lapses he had found in the

German clergy as they acquiesced to Hitler.

Back when I was attending homeschool conferences, more than

a decade ago, I heard Pastor Voddie Baucham speak. He defined having a Biblical

worldview as believing in Jesus, who lived a perfect life, died for us, and

suffered for our sins as our Savior. That is what I believe, and that is

doctrine in my religion, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. So I

was shocked when he told us that less than 10% of professed Christians have

this Biblical worldview, and only 51% of pastors have it. I think that’s

evidence of the infiltration.

I heard a talk recently—I think it was Ken Ham telling a

story from his childhood, but I could be wrong about who it was. Anyway, he recalled

the pastor had been telling the story of the feeding of the 5000 with the

loaves and fishes. The pastor had explained that, once a young boy had pulled

out his meager amount of fish and bread to share, it had incentivized everyone

else to share what they had, and then there was plenty. The storyteller’s

father went up to the pastor afterward and told him, “That’s not what happened.”

The pastor had taken the miracle out of the story, along with Jesus’ divine

power. And he’d made the story pointless. If enough people had brought food and

to spare, there was never anyone in need of being fed, so why would the story

even show up in scriptures? More likely, it was remarkably miraculous, and

that’s why it got recorded. Church leadership that doesn’t believe in the

divinity of Christ means they are not Christian, and they are leading the flock toward something else that is not good.

What Behling said had taken place in the infiltrated churches was a replacement of the divine doctrine with the “Marxist construct of oppressed versus oppressor”; in other words, social justice—even though it took until recent decades for them to start using that term.

Matsen and Behling got into a section where they were

discussing some various flavors of authoritarian tyranny.

I’ll share some of the transcript here, so you can see the attempts

to define various forms of authoritarian tyranny. [GB is Greg Matsen, and JB is

Julie Behling.]

GM: I’ve noticed in reading your book—obviously I don’t know

about the documentary yet—but in the book you use the term Communism quite a

bit. That’s kind of a term that isn’t used as much. It’s Marxist, maybe, or,

moving on to 2.0 here with woke, etc. You have a background in studying Communism,

right?

He asks her about the terms, so she begins with some

definitions:

·

Socialism is when the government owns the means

of production and is in charge.

·

Communism is when the government owns the means

of production, and this government is instituted through a violent overthrow of

the previous regime.

·

Marxism is the oppressed versus oppressor

construct that's the playbook for preparing a society to fall to Communism.

JB: So if you can identify a group of people who either are

oppressed or who can be made to feel oppressed, you can rile them up to anger

and stoke the grievance and say, “Hey there's your oppressor. Tear down that

system of power.” The systems of power are torn down and weakened, and now the

Communists can come in and assume authority.

This caught my attention, because I have this in my basic

article about the Spherical Model:

People tend to be afraid of the chaos of anarchy. Lenin saw this. One way to gain totalitarian power is to create chaos and then promise to solve the problems of chaos (crime, poverty, lack of safety on all levels) by offering government solutions, until the revolutionaries have managed to get themselves installed as dictators. This was the purpose of Trotsky’s idea of perpetual revolution: Place power in our hands, and we will see that you are fed and housed and protected—that is, if the dictator was so minded once the power was achieved. Everywhere that Communism has been tried, it took hold because people gave in to this desire for government to provide protection and food and shelter. It works on a people who do not trust their own ability to provide, and it works especially well when chaos reigns to make it difficult for people to provide for themselves. Revolutionaries therefore cause anarchy so that they can implement their own totalitarian tyranny.

I think Behling is right when she is saying that the

oppressed versus oppressor tactic is to create chaos that will allow the

tyrants to step in and take control.

Behling says, “What we have brewing here, it's not exactly

like the type of Communism that the Soviets had. It's worse.” Matsen asks her why

it’s worse.

JB: Because it's more crafty. And it's more like the

Communist Chinese system, where it's this weird marriage of Communism and

Fascism and then, honestly, a little bit of Monopolistic Capitalism thrown in

for good measure. It's the most abusive forms of government fused together with

this—what they're hoping for—Global Leadership with all the technocratic

controls that they— we now have with being in the 21st century, and it's truly

frightening.

The Spherical Model allows us to see the relative badness or goodness of a philosophy graphically. You can determine how close the ideas bring society to freedom, prosperity, and civilization, or alternatively how close they bring society to tyranny, poverty, and savagery. For a fuller discussion see this summary. Or, for more detail, see all the articles on the website, starting with "The Political World Is Round."

|

| The political, economic, and social spheres of the Spherical Model |

There are slight flavor differences between Communism, Socialism, Fascism, the overarching philosophy of Marxism, as well as what Behling calls Monopolistic Capitalism—another way of saying Oligarchy or rule by businesses and controllers of money. These are all southern hemisphere on the Spherical Model, mostly on the statist side, or controlled by the government, although some (oligarchs and organized crime possibly) on the chaos or anarchic side of tyranny. But they’re all bunched together, down toward the bad pole of tyranny.

|

| Fascism, Socialism, and Communism are all statist tyrannies, and thus they take up approximately the same location on the Spherical Model. |

There’s discussion about the way tyranny—Marxism, Communism—is

being presented here in the West, particularly in the US. It’s like a virus, or

a cancer, that spreads. But, because the West was healthy (not a lot of abject

poverty), it was hard to convince a poor class to rise up in rebellion,

allowing for the tyrannical takeover.

JB: Communism—you can see it as a virus, or as a cancer, and

it spreads to various parts of the—different organs and different systems, and

eats it up, and takes it over. And, you know, Antonio Gramsci, his whole plot,

you know, he was back there in Italy as a Marxist, and very stressed out that

the West was not falling to Communism, in the 1930s. And so he’s the one who

came up with cultural Marxism, and said, “OK, we’ve got to infiltrate these

cultures—the West has this cultural hegemony that is resistant to Communism;

we’ve got to go in and take those things over.”

I mean, before the businesses could be taken over, our

culture was already taken over to a good enough extent that that was possible.

So, yeah. We’re in a very late stage, because it’s far beyond the culture at

this point.

There’s a part of the book of Revelation that I’ve been looking at, in chapter 13, about the beast that rises up out of the sea. This beast has multiple heads and crowns. Symbolically, it seems to be the various powers reigning around the world, and interconnected together as one “beast.” One of the heads is mortally wounded—but then comes back to life. I have looked at this and wondered if this is Communism, or one of the other words we’ve listed and defined above. We fought a World War to wipe out this attempt at controlling all the peoples of the earth. We said, “Never again!” And yet, here we are, with our college campuses preaching the Gramsci version, cultural Marxism, where everyone is either oppressed or oppressor. There’s an attempt to control our ability to make a living, or to buy and sell, based on whether we have bought into this party line. It’s as ugly as it ever was. “We’re in a very late stage,” Behling says.

|

| "La Bete de la Mer," a French tapestry showing John the Revelator, Satan the dragon, and the sea beast of Revelation 13. Image from Wikipedia. |

Matsen, at one point, adds this:

GM: I really like that you said that they’re using Fascism,

because that’s 100% true. It’s so funny, because they call anyone who leans

right of them, which is almost everyone, a Fascist. What a Fascist really

means, they’re using business; they’re using the current institutions, right,

that are not owned by the state. And that is Fascism. And they’re using it

better than any Fascist has ever used it before. And so, again, that’s the idea

of adapting to the West and using their system, where now they are the Fascists

that are, again, infecting and using and coercing the free enterprises to—and

free organizations and institutions in the West—to tow the party line.

Behling tries to give us some hope. I mean, why point out these things if there isn’t any hope of recovery?

JB: And I really do have hope—I mean, I’m a little bit doom

and gloom here—but I do have hope that there are so many good people, so many

good Christians, so many good people who love freedom that, if we can wake up

enough people, we have this window of time right now—if we can wake up enough

people—that these agendas will not be able to come to full fruition. That is my

hope.

There is some reason to hope. I know so many good people, as

she does, so many good Christians and also good people of other faiths, who

love freedom, and truth, and want to preserve our God-given rights. Governments

are instituted to protect those God-given rights, but government is fire, and

it seems to fuel itself and grasp power unto itself that it hasn’t been given

by the people.

One purpose of the Spherical Model is to clarify. It isn’t

necessary to understand all the nuances and differences among the various words

we use for tyranny. It’s only necessary to know whether something leads to

Freedom, Prosperity, and Civilization, or whether it instead leads to Tyranny,

Poverty, and Savagery. Those things are ascertainable with a few basic questions—and a lot of truth.

May this coming year be a year where we bring more people to

an awakening, with truth—offered with love and caring, but always by giving and

sharing truth.