It’s almost Christmas Eve. I wrote a bit about Christmas a couple of weeks ago. This piece isn’t as joyful. But it is also about that little part of the world we think about this time of year, because it is where our Savior was born.

This is something of a book review. A friend recommended the book The Lemon Tree, An Arab, a Jew, and the Heart of the Middle East, by Sandy Tolan. There’s a house, with a lemon tree, that has a complicated history. It is a real place. The version I read was a young reader’s edition of an award-winning adult book. This one was 228 pages, so I didn’t realize it qualified as a “children’s book,” until well into it. Or maybe during the afterword. But this one will do.

|

| book cover from Amazon |

The original book was published in 2006, which started out

in the form of a 43-minute radio documentary on NPR’s Fresh Air, in

1998, at the occasion of the 1948 Arab-Israeli war. The afterword of this

version shows events up through 2013, and it was published in 2020.

The purpose of the story, I think, is intended to show that

a friendship can exist between two natural enemies, when the people are willing

to really listen to one another.

That’s the first impression of the story. But there were

several niggling details that didn’t seem right. And an ending that didn’t

coincide with that message. So I’d like to take a look at this story,

particularly in light of what is happening in that place now.

The house was originally owned by the Khairi family,

Palestinian Arabs. Their son Bashir is one of the two main people in the story.

The house is later inhabited by the Eshkenazis, a Jewish family relocated from

Bulgaria. Their daughter Dalia is the other main person in the story.

There’s a fair amount of history told at the beginning of

the book. The book claims to be nonfiction in every way. Well-researched, we

are told. There are maps at the beginning, showing various plans.

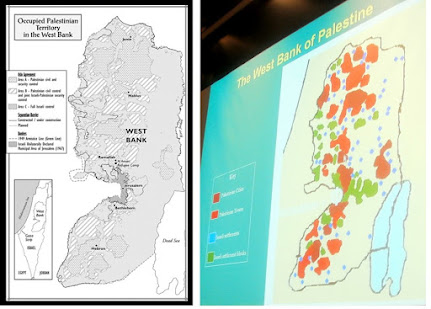

|

| Left map is from the book. Upper right is from this Danny Ayalon video, and lower right is from this Prager U video. These both show that the original protectorate welcoming Jews to Israel was considerably larger than any later boundaries. |

The maps match the history, but some details do not coincide

with the history I know of this region. It’s a difficult thing to understand

one another and come to some sort of agreement when we are dealing with “facts”

that simply don’t match.

According to the book, the Israelis—the Jews—are always the

aggressors. They are brutal and unfeeling, and aim for civilians. That is the

story people tell when they want you to hate the Jews. In reality, it is hard

to find a people anywhere in history who have gone more out of their way to

avoid civilian casualties in their wars. And the wars on their part have always

been defensive—including the one that started October 7, 2023.

Whenever you have someone referring to Israel as “occupying”

the land, you know you are reading a biased, anti-Jewish source. No amount of

pretending to be thoughtful passes the smell test.

So, what is the story of this house with the lemon tree? According to the family story, this is 1948, the war Israel had to fight one year into its existence following its creation by the United Nations, following the end of WWII and the holocaust. Jews, who were already living in Israel (some Jews had lived there throughout the centuries, but in growing numbers in the 20th Century), were joined by refugees from many parts of Europe, where it was no longer safe for them to live.

|

| Left map from the book. Upper right from Danny Ayalon video. Lower right from PragerU video. While the maps are essentially the same, the book fails to note that these boundaries, while greatly shrinking Israeli land, were accepted by Israel but rejected by the Arabs, who went to war within the year to wipe out Israel. Israel won, but the Arabs never accepted these nor any other boundaries. |

They did not come to a nation called Palestine; they came to an area, given that name anciently by the Romans. After the defeat of the Ottoman Empire, this area was a protectorate of Great Britain. Much, but not all, was uninhabited. The Jews, coming from the diaspora, did not oust any current residents. They came and settled, building their own communities—buying land whenever it had an owner. The Arabs living among them started protesting their presence with terrorist attacks at least as early as the 1920s. But there wasn’t always animosity. Jews and Arabs mainly did business together, as they have done in other Mediterranean areas over the centuries.

But when Israel was made a state, with worldwide agreement and treaty, in 1947, the Arabs surrounding the newly birthed tiny nation rebelled. And started a war. Which Israel miraculously won.

During this war—as with others since then—the Arabs call for

the Jews to be removed from the nation that has been their homeland for more

than three millennia. Every time Israel has been willing to negotiate a

partition—always with Israel giving up land—the Arabs have refused, insisting

instead on Jewish annihilation.

So our story with Bashir’s family begins during this 1948

war. In the book, a Jewish neighbor rides into their fields and warns them the

army is coming, and they need to get out or be killed. They grab what they can,

as do their neighbors, and they flee. While they are concerned, they are

certain the Palestinian Arabs will quickly win the war, and then they can

return to their homes.

I have read about this before. I can’t verify that a

neighboring Jew didn’t call out to them. But in general the Arab aggressors

were the ones calling for the people to clear out, so they could go through the

streets without having to separate out the enemy; they could just

indiscriminately kill. The Jews were telling people, “You don’t have to leave.

If you want to live peacefully with us, we will not harm you.” They kept their

word to those who stayed.

But those who left—think about what they have done; and this

includes Bashir and family. They have declared allegiance to the enemies of the

nation. They have declared their desire for the annihilation of the people

granted nationhood. Their side loses. And they have not changed their designs,

but they think their enemies should let them back in, to fight them from within

another day.

Refugees went several directions. They continued terrorist

attacks from wherever they were. The neighboring nations that took them in

could tolerate them only so long, and then they ousted them. So there are

pockets of Palestinian Arabs, mainly in Gaza, west and south of the rest of

Israel, and another portion to the north. You might notice that there were

Jewish refugees at that time as well—who fled into Israel from

neighboring countries. They aren’t still refugees, of course; they are Israeli

citizens. I don’t know of another incidence in history where refugees have been

kept in refugee settlements—temporary, subsistence level—without being allowed

to become permanent anywhere, for decades on end. They are not held in these

settlements by the Israelis; the Israelis only police their own borders, not

the rest of the world, which is keeping those people trapped in poverty.

This point is important, because it’s what the story turns

on.

After 20 years, Bashir, now in his mid-twenties, returns, along with his cousins, to visit their former homes. At Bashir’s home Dalia Eshkenazi decides to overcome her fear and open the door to them. They note that the lemon tree Bashir’s family had planted is still surviving. Something of a friendship ensues. Dalia believes the way Bashir tells it—that the Israelis forced his people out and then wouldn’t let them return after the war. Dalia is horror struck. She had always understood that the people had simply abandoned their houses, although she couldn’t understand why. This changes many things, she believes. Her people were in the wrong, although after all these years, what is there to do? She in fact does many things. After inheriting the house in adulthood, she turns it into a school for Arab children. And she continues a long correspondence with Bashir, and later with his family.

|

| Left map from the book. Upper right from Danny Ayalon video. Lower right from PragerU video. The story of Bashir's first visit to Dalia's family is about a year after the 1967 war, during which all the surrounding Arab nations attacked, but Israel miraculously won. The Arabs continued to refuse to accept any borders that acknowledged Israel as a nation. |

Bashir, for his part, while supposedly trying to deeply

understand, also tells Dalia that the Jews should all return to where they came

from. He simply doesn’t hear, or understand, that there is nowhere but Israel

for the Jews to return to. He thinks he is being generous to exempt those Jews

who were born in Israel prior to 1947. But, of course, they shouldn’t have any

right to rule in the land the Palestinians now claim to own—and accuse the

Israelis of “occupying.”

Despite this peacemaking friendship, Bashir is a member of

the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, or PFLP—a terrorist group

intent on ousting the Israelis and “returning” all the land to the Palestinian

Arabs. Over the years he is arrested multiple times. I forget how long he spent

in prison, but I think the longest stint was 15 years. In the afterword, in

2011, he is arrested and interrogated for several days, at age 69, following an

attack a few weeks earlier in which an Israeli family was brutally murdered,

and which had been linked to PFLP members in the vicinity. Up through this

time, he answers as he always has: “I am a Palestinian who believes in the

Palestinian cause. And I despise the occupation. The crux of the Palestinian

cause is the right of return. Otherwise there will be endless bloodshed.”

By this time he has stopped his correspondence with Dalia,

because she did not follow through with his demand—that she “petition the city

of Ramla to return the old Arab houses to their original Palestinian owners.”

This was not something she had either the power or ability to do. So he has shunned

her.

As I look at the story, Dalia is the peacemaker. The Jewish

peacemaker. Bashir is the violent, angry, demanding Arab, who never does

understand either what really happened, or what is reality after all the

decades. There can be no peace, because people like him do not want peace; they

want the Jews disposed of.

The book doesn’t tell the story the author intended. It is,

rather, a metaphor for the larger conflict. A Jew opens the door to peace; a

Palestinian Arab makes unreasonable and irrational demands that cannot and

should not be met.

In the afterword, the book gives this account of casualties:

Since

Dalia and Bashir last saw each other, in 2005, multiple wars have devastated

Gaza, killing more than 3,200 Palestinian civilians, including more than one

thousand children, mostly killed by Israeli air strikes. During that same time,

twenty-nine Israeli civilians died from Hamas rocket attacks launched from

Gaza. None of those were children. Yet, despite the dramatic disparity in

casualties, throughout Israel, and in the media, Palestinians are often

portrayed as the aggressors, and Israelis, the victims.

The author fails to note that it was Palestinians who began every war, every attack. Every Israeli air strike was in defense, not offense. And Jewish leaders went to great lengths to warn civilians to get safely away from where the air strikes were targeted to land. Meanwhile, Palestinian leaders placed civilians in harm’s way, on purpose, to be able to blame Israelis. And their attacks have always aimed at civilians. The disparity in deaths is attributable almost entirely to Israeli military strength, including the Iron Dome defenses—not attributable to some gentle kindness by the Palestinian attackers.

In a follow-up to the last time I talked about the war, I

wondered what the casualty count is at this point. Oddly, it isn’t that easy

to ascertain. There are a number of articles detailing casualties in Gaza.

Getting an updated count of casualties in Israel, which has been under

continual rocket attacks—except for a brief cease fire around November 21, in

which there were negotiations for prisoner exchanges—has not been easy.

When the attack first happened, horrifying the world, we learned,

“On 7 October 2023, 1,139 Israelis and foreign nationals, including 764

civilians, were killed, and 248 persons taken hostage during the initial attack

on Israel from the Gaza Strip.”[i]

Note that the Israeli casualties on that day equal a third of the Palestinian count

recounted in the book that stretched over a couple of decades.

It took until about the first weekend of the war before the

concern turned from the savagery of the terrorist Palestinians to concern that

Israel might use its military might to stop their enemies—which might, as it

turns out, cause casualties, including civilian casualties, despite Israel’s

efforts to avoid them.

Let’s use an analogy, something like that house in the story,

but here in Texas. Suppose there’s a house that is broken into; the intruders intend

to take whatever they can get hold of, and they have no compunctions about

killing any residents who might stand in their way. But, while they should be

aware that homeowners are well-armed in Texas, they seem shocked, Shocked! that

the homeowner pulls out a gun and shoots at them. One of the intruders is

killed; another is wounded. The wounded thief calls on the media to condemn the

homeowner who protected himself, his family, and his home. He had greater

firepower—a hunting rifle, as it turned out—which overpowered the mere handguns

carried by the intruders. Not fair! The homeowner valued his own life

and property as more valuable than the thieves', who were only breaking into his

home and threatening him, and hadn’t yet succeeded in killing him and his

family.

That kind of argument might work in California or New

York—places where people aren’t allowed to own guns to protect themselves. But

it doesn’t make sense in Texas. We have what is called the Castle Doctrine,

meaning a person has the right to protect himself—with lethal force if

necessary—on his own property when under threat.

Do we feel bad for the intruders? One was killed. Another

wounded. We would rather that hadn’t happened—but it was entirely preventable

by the thieves; all they had to do was not to break into the home to rob and

plunder.

We can feel bad for Palestinians, many of whom are trapped

in poverty and bad circumstances—and yet are not terrorist aggressors. But they

live among such aggressors. They vote them into power. And they continue to

claim the Israelis have no right to live in their own country and to protect

themselves.

There might be two points of view. But it might be that one

side is completely in the wrong—and they are the ones who have the power to

cause peace in the Middle East. If only they were willing.

[i] "Israel social security data reveals true picture of Oct 7 deaths." France 24. 15 December

2023. Archived from the original on 17 December 2023. Retrieved 18 December

2023. The quote and citation were found on Wikipedia December 22, 2023.

No comments:

Post a Comment