I’ve been traveling the last couple of weeks, visiting old

friends. This meant a lot of conversations about families, children, and

grandchildren. But it also included, in this presidential election year, the

occasional conversation about who to vote for.

In my circle of friends in which it came up, no one is

willing to vote for Hillary under any circumstances. Almost no one is willing

to vote for Trump. So the question at hand is, who will you vote for? For me,

it’s down to three options: leave it blank, write-in Ted Cruz, or vote for

independent candidate Evan McMullin. I was a bit dismayed that most were only

vaguely aware of McMullin: “Is he that CIA guy?” Still, he’s gone from zero up to 9% in a few weeks,

and he’s just getting underway. So we’ll see.

But what I really found disheartening was how much negative

belief there was about Ted Cruz among friends who claim to be conservative and

supportive of the Constitution.

One friend disliked how Evangelical he sounds. I don’t know

if I’m just acclimated to that living in the South (same town Ted Cruz lives

in). But I hear the passion for the Constitution. When I talked about Cruz’s

history, memorizing and presenting on the Constitution hundreds of times as a

teen, that was new information.

That surprised me, because I was aware of that detail well

before Cruz declared for the presidency—heard it from his father, speaking at

our local Tea Party meeting. If there’s a single thing to know about Cruz, it’s

how strong he is on the Constitution, both his understanding of it and his

resolute commitment to it. But that essential detail about Cruz apparently didn’t

get passed along in media a few states away.

One conversation went something like this:

Friend: I don't like Ted Cruz. He scares

me.

Me: He does? What’s

scary about him?

Friend: He’s so

extreme.

Me: Really? What

part of the Constitution do you find extreme?

Friend: Not the

Constitution. I’m for the Constitution. I just don’t like his approach.

Me: What do you

mean by his approach?

Friend: He’s just

so negative. He blocks everything.

Me: You must be

thinking about the claim that he shut down the government. But you know the

budget originates in the House, and Cruz is in the Senate, so he had no power

to shut down the government.

Friend: Yeah, but…

Me: I think you’re

responding to the media says about him.

Friend: No, I don’t

think so. I just know in my gut, he’s so negative. And Mike Lee. I hate that

guy.

Me: Really? I

think Mike Lee is great. I think we’d do well to have him as a Supreme Court

Justice, but we need him in the Senate.

Friend: No. I hate

the way they block everything.

Me: What part of

the Constitution do you think they shouldn’t stand firm on and just give in?

Friend: I can’t

make the argument. I just feel like they’re too extreme.

Don’t worry; it ended well. I learned from the exchange. It

wasn’t about either of us trying to convince the other, and that’s a good

thing, which was true of all of these brief political conversations with

friends.

So here’s my conclusion from this nonscientific survey: Among

people who sense we’re way too far from freedom, prosperity, and civilization,

but who get their news from snippets of TV, radio, and minimal research, and

who don’t spend a lot of time thinking through the arguments because their

lives are full, they believe standing firm on the Constitution is now extreme.

This does not bode well for the future of America.

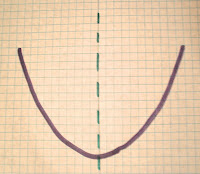

I think the Spherical Model can help, because we use different

language than the media uses. We don’t talk about right or left, with extremes

either way.

|

| The Political Sphere |

Extreme,

translated through the populace, means “not in the norm for the reporter of the

information.” Since 90% or more of mainstream journalists vote democrat and

therefore do not understand and value the Constitution, normal for them is well

outside the freedom zone.

What we seek is the particular, the special, the often rare—the

good.

Politically, this means freedom, or liberty. It means the

person who decides what to do with his life is the person himself, not some

overseer or ruler. We have the right to our own life, liberty, and property.

In world history, that freedom, that self-sovereignty, is

quite rare. Most humans have experienced some level of tyranny—under

monarchies, socialism, communism, fascism, tribalism, or feudalism; led by

kings, emperors, dictators, tribal chiefs, crime bosses, or some other form of grand

or petty oppressor.

All of those possibilities are south, toward tyranny and

away from freedom. Some are southeast, because they’re statist (governmental)

tyrannies. Some are southwest, because they’re chaotic (non-governmental)

tyrannies. Some are further south into tyranny than others, depending on how

much freedom they deprive people of. There’s a whole array—a whole hemisphere—of

forms of tyranny that media, academia, and much of the world would find normal

and therefore not extreme.

The only extreme

that really matters is the distance from the freedom zone. Extremely far south

is an extremely bad thing. South at all is worse than it needs to be. We don’t

have to be stuck there, despite what history has tried to convince us.

We know the principles that lead northward. We need to go there no matter what the

masses who think freedom, as guaranteed in our Constitution for example, is

extreme in a negative way.

We need to find better ways of saying what we mean, because

perfectly good words like conservative

have been redefined to mean anti-freedom, even bigoted or hate-filled—and extreme.

Instead, we can say we want to go north, to the freedom zone, where we

mainly govern ourselves, with government limited to its proper role of

safeguarding our life, liberty, and property.

While we’re at it, we also want to go north economically to

prosperity, away from poverty. And we want to go north to civilization, away

from savagery. Both of those have been called extreme too.

|

| The Political Sphere, Economic Sphere, and Social Sphere, the three layers of The Spherical Model |