The poppy is a symbol of the fallen. It relates to a poem, “In

Flanders Field,” by Lieutenant Colonel John McCrae, channeling the voices of

the fallen soldiers, buried under the hardy bright flowers. The poem was

written in 1915, and spread widely prior to McCrae’s death in early 1918. A

woman named Moina Michael read the poem in a magazine just two

days before the armistice, and was inspired by it. She wrote a poem, “We Shall

Keep Faith,” in response, and vowed to always wear a red poppy. She came up

with the idea of making and selling red fabric poppies to raise money in

support of returning veterans.

Although the poppy was originally associated with the

armistice, in America we don’t typically wear poppies on Veterans Day; we honor

the fallen on Memorial Day, in May.

There aren’t any WWI veterans still alive, now, after a

century. And there are only about a thousand WWII veterans still alive, with an

average age of 95.

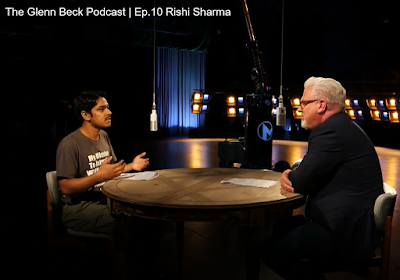

This past Saturday’s Glenn Beck Podcast featured a young man, Rishi Sharma, age 21,

who has made it his life’s mission to document the stories of the remaining

WWII combat veterans. He tries to interview at least one a day. He started in

high school, mostly going to local rest homes. And then expanded, eventually

starting a GoFundMe page to make it possible. He mostly lives in his car,

driving from place to place, making friends with veterans. If you want to help

contribute (monetarily, or by doing interviews), you can go to Heroes of the Second World War.

|

| Rishi Sharma on Glenn Beck podcast, screenshot |

We shouldn’t have to wait for an obituary to find out about

the most amazing and heroic people that live in our community. You know, we

should be able to talk to them. We should be able to learn about it while

they’re still alive, so that we can talk to them, and look them in the eyes,

and thank them. And, you know, interact with them.

There are just so many interesting obituaries that you find,

you know, that I find as I’m trying to find the veterans. But there’s no

interviews of them. And I’m wondering to myself, here is this veteran that’s

been able to live into his 90s and 100s, and no one took the time just to document

his story? You know, all those sacrifices and moments of his life have not just

been put into three paragraphs? They don’t deserve that.

I mean, they deserve a voice in our world, and our future

world, because I think the best thing that we can do for 410,000 boys who were

killed in the war—and everyone who was killed in the war across the world—is

give their death some meaning. Because if we just pretend that that was a long

time ago and it doesn’t matter, and continue to act the way we’re acting now,

we’re literally spitting on the graves of those men.

Because, it’s bad enough that they had to die at 18, 19,

20—you know, the fact that they were born, had the middle of their life and the

end of their life both before they could even drink alcohol—you know, that’s a

really sobering thought. But, it’s bad enough that they had to be killed, but

it would be even worse if they were killed for no reason. And I really hope

that the veterans who I interview, who say that their friends have died in

vain—I really hope that they end up being wrong, and that their friends died

for a purpose.

Because, I mean, it was just 75 years ago, which is such a

short time in the span of humanity. And, I mean, it should still be relevant

and raw. I mean, I just don’t understand why people don’t talk more about it.

If we’re going to be a civilized people, it is required of

us to honor those who have made our freedom possible. That is something we all

ought to be able to agree on.

At a time when it’s so easy to be disagreeable, there was a

response this weekend that I thought was helpful. If you’ll remember, a week

earlier, on Saturday Night Live, a comic had mocked congressional candidate—now

my new Congressman—Dan Crenshaw, who lost an eye to an IED in Afghanistan, on

his third deployment (he deployed twice more after recovering the sight in one

of his eyes). The response, on SNL this week, is worth seeing, below. It’s fun. After the humor,

Dan is able to say what veterans really want to hear. He suggests that, while

saying, “Thank you for your service” is good, he’d like us to say—well, I’ll

just use his words:

There’s a lot of lessons to be learned here. Not just that

the left and the right can still agree on some things, but also this: Americans

can forgive one another. We can remember what brings us together as a country

and still see the good in each other.

This is Veterans Day weekend, which means that it’s a good

time for every American to connect with a veteran. Maybe say, “Thanks for your

service.” But I would actually encourage you to say something else. Tell a

veteran, “Never forget.” When you say, “Never forget” to a veteran, you are

implying that, as an American, you are in it with them, not separated by some

imaginary barrier between civilians and veterans, but connected together as

grateful fellow Americans. We’ll never forget the sacrifices made by veterans

past and present, and never forget those we lost on 9/11, heroes like Pete

[Davidson]’s father. So I’ll just say, Pete, never forget.

No comments:

Post a Comment